By Mackenzie Kwok

In June, the United States recognizes Pride Month. In August, communities across the US also recognize Black Pride as its own unique and significant celebration of Black LGBTQIA+ folks who often go unrecognized during June’s celebrations. New York City Black Pride is an annual five-day event centering the contributions and achievements of Black and Latino LGBTQ+ communities.

We spoke with Michael Roberson, an educator, theologian, and House Ballroom community organizer who partners with ArtsWestchester on House Ballroom Arts events, supported by Mid Atlantic Arts’ Folk and Traditional Community Projects program.

Display caption

Image: The Legendary House of Xclusive Lanvin: On and Off the Runway program flyer. Credit: ArtsWestchester.

Introduce yourself!

I am Michael Roberson. I’ve been doing public health and sexual health for the past 31 years in HIV prevention and research, particularly targeting Black and Latinx LGBTQ communities and the House Ballroom community. I have been a member of the Ballroom Community for about 30 years now. I also do race, sexuality, and theological work through the Center for Race and Religion and Economic Democracy. I went to Union College Seminary, and now I am a member of an international sound art collective called Ultra-Red that emerged out of the AIDS political movement ACT UP.

What is House Ballroom culture? Who are the communities involved?

I’m going to start present and move backwards in time. A great friend who is no longer here, Kai, whose shoulders I stand on, was the mother to help the very first public health HIV intervention targeting the Ball community. He used to say, House Ball is not just about houses, necessarily. It is a social network.

House Ballroom emerges out of the drag ball circuit. It’s difficult to singularly define what it is, since it’s grounded in a community of oral tradition. In many ways, it emerges during the Harlem Renaissance and drag balls. For me, Ballroom is a global movement. It’s a collective of people who are predominantly Black, Latinx, LGBTQ, in the US context, who come together to compete at balls. For me, Ballroom culture is also a radical community organizing initiative, and a Black theology.

How is Ballroom Culture a form of Black theology?

I went to Union Theological Seminary to put theology in conversation with public health because the theology of abomination had direct impact on health disparities. The theology of abomination stems from homophobia. It claims that LGBTQ+ folks are situated outside of the image of God. This theology has dispossessed folks away from structures of care and belonging, leading us to believe our bodies have no value. This has had devastating and damaging effects on the lives of Black gay men, particularly those living with HIV. I saw that Black gay men and trans women were beginning to think that we were predisposed to becoming HIV positive. I wanted to change that narrative. For me, this community has to be theological because there is nothing else you can tell folks who have been told they’re no good to God.

For me, Ballroom is a theological discourse as a contestation to the Black church. What does it mean for Black people moving from the South to the North, looking for new spaces of freedom, only to be unfree in the North? Ballroom gives us a new free space when the church rejected LGBTQ Black folks.

So many things created as part of the Black gay infrastructure historically came out of the AIDS crisis. If not for the AIDS crisis, would we even have agencies we have? But Ballroom began organizing itself prior to AIDS. Ballroom was the most effective countercultural community.

Why is it important to highlight Ballroom as traditional knowledge?

Ballroom is an oral traditional community that has had such a rounded history. It has not been allowed to be considered part of the lexicon of movements of historical art and art expressions. Ballroom was and is in conversation with other artistic movements like hip hop, like the Nuyorican poet movement during the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, when the city was at the brink of bankruptcy. Ballroom is a theological formation that has cultural products. It’s grounded in oral tradition.

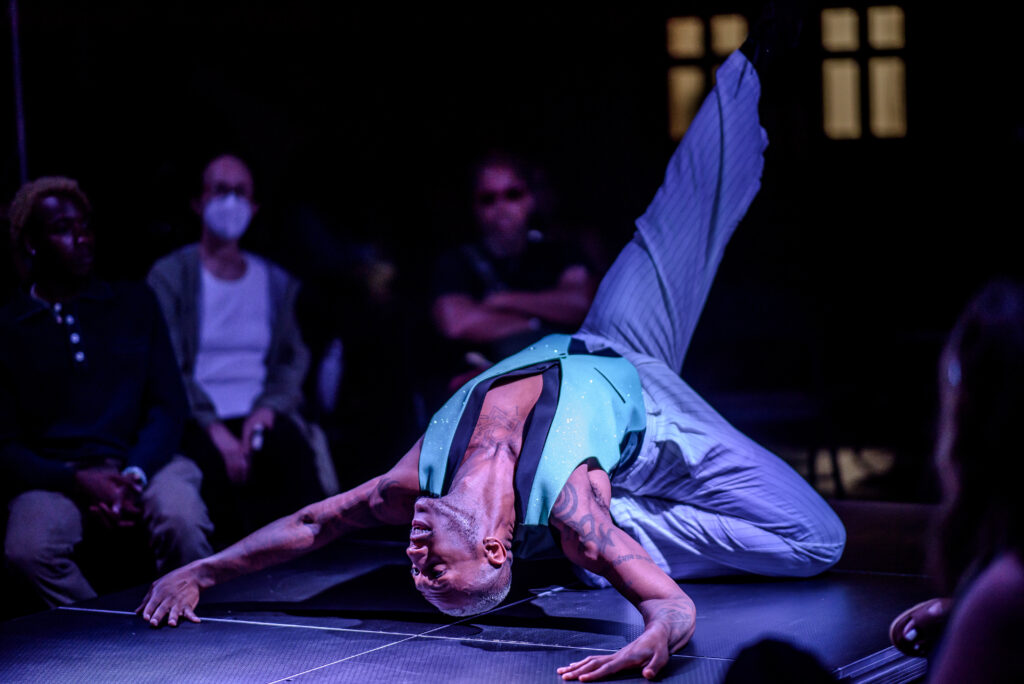

Display caption

Image: Legendary Khaos Lanvin’s vogue femme performance during the Folk & Traditional Arts Community Projects grant-funded program “Ballroom has Something to Say: An Ode to Black Gay/Queer Men.” Credit: Susan Naqib.

What is the role of mentorship and intergenerational knowledge in House Ballroom?

Mentorship and kinship are crucial to the generational transmission of traditions. Up until recently, we did not think we were that important, that our practices were significant. Ballroom is grounded in oral tradition and intergenerational knowledge. When you are queer and you have been told that because you are Black or Latinx and LGBTQ, the things you do and say mean nothing. Through kinship, mentorship and intergenerational transmission of traditions, we realize that we are important. We are significant.

In 1967, Crystal LaBeija walked off stage in protests around racism and colorism in drag balls. She was the only African American drag performer who went back to the old Harlem drag ball circuit. She and other trans women created the House of LaBeija. A lot of people think she created drag balls, but she didn’t. She convinced people to create a House structure, with a mother, father, and children as community’s constructs. It was also responding to communities who were ostracized from their families of origin.

When folks were ostracized from their families, people had to stay with other folks, particularly when the AIDS crisis hit. The mothers and fathers of Ballroom had to take care of their children. In fact, when people passed away, mothers and fathers were elders of the community. Elders could have been someone as young as 25 years old.

When you are inducted in a House, the question is: what will you do for the community? How are you giving? When I arrived into House, about 30 years ago, there were only four statuses: up and coming, statement, upcoming legend, and legend. Now, we have icons, pioneers, and legends. You are a legend if you have given back to the community.

The mothers of a House had to organize and get people money, hold services for people who died from HIV. In New York specifically, we saw so many House members involved in public health and community organizing. We saw mentors training younger folks to respond to some of the disparities facing our community.

My kinship daughter, Doctor Jennifer Lee, was the Deputy Executive Director at the HEAT (Health & Education Alternatives for Teens) Program. We were doing national organizing initiatives in 2016, and she got money to create something called House Lives Matter. This was new—we wanted to lift up the Black Lives Matter movement for what it was doing, while critiquing why nothing had been done about the Black trans women who had been brutalized. This is a national leadership initiative to address intersectional disparities impacting the community.

My son, the Icon Pony Zion created Vogue Evolution, a Black and Latinx LGBT dance initiative. He wanted to be able to do HIV prevention and social justice to the art of vogue dance. We created this thing called vogue theory in relationship to it, which takes a theoretical framework of vogue as praxis to develop young folks’ leadership skills.

What is Black Pride? Why is it important?

It is important to call attention to this. Black Pride as a history began in the late 1980s in Washington, DC. Black LGBTQ folks were not being seen in the larger Pride in June. New York City Black LGBTQ+ Pride started in 1995. I was in charge of New York City Black Pride from 2003 to 2007. We used to throw the Heritage Ball, and there was a free HIV prevention organization ball that was a part of that. It is so grounded in community.

What do you hope people take away from the House Ballroom events with ArtsWestchester?

It depends on the audience. I want to challenge how people have traditionally believed what Ballroom means. We are a community that, in the US context, are for the most part descended from enslaved people. We have been told that our bodies are for commodity, that to perform for others’ gazes is to be legible. It is my desire to push folks to understand performance as politics and theology. How have we been told about our body only being valuable for the gaze of hegemonic power? I want to show that balls are politics 101: they organize people together at an event. While so many political movements organize around crisis, they don’t sustain themselves. But Ballroom organizes around joy in order to address crisis, so this is a political movement that can rejuvenate itself.

Another thing is that archiving is important. Archiving is not something we used to think about, or we did not really think that the work we were doing is archival work. We have been told that our knowledge production was not worthy to archive. But now, we’re beginning to see a lot of throwbacks, people having videotapes from before. We have been archiving for years, and many Ballroom documentarians and archivists have held viewing parties. At these parties, House Ballroom Community members gather to critique, study, analyze, and enjoy video footage from past balls. Other Ballroom Community members have drawn from archival video footage for documentary films, like the recent film I’m Your Venus (2024). Our work is starting to become recognized as archiving.